To listen, click here .

Ray Pennings on Sirius XM Canada

April 17, 2017

Canadians may be vacating the pews but they are keeping the faith: poll

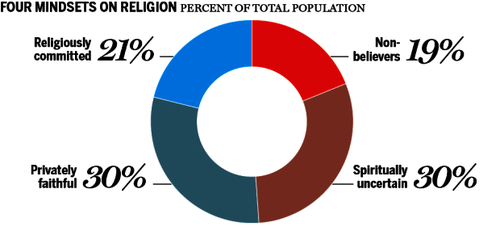

Beneath Canadians’ widespread abandonment of places of worship and their negative view of even the word “religion,” a new poll has found a solid core of faith that continues to shape the country. The survey, conducted by the Angus Reid Institute in partnership with Faith in Canada 150, grouped respondents into four categories according to their answers on a range of questions gauging their beliefs and religious practices. “We have a society that has a secular government and there is a general assumption of faith being very private,” said Ray Pennings, executive vice-president of think tank Cardus. “On the other hand, when you actually take a look at everyday society, the majority of people are people of faith to one degree or another, and faith informs and influences many of the ways we deal with each other on a day-to-day basis.”Mike Faille/National Post//Angus ReidThe poll classifies 21 per cent of Canadians as religiously committed, meaning they hold a strong belief in God or a higher power and regularly attend religious services. At the other end of the spectrum, 19 per cent of Canadians are pure non-believers. It is the swath in between, equally divided between what the pollster terms “privately faithful” and “spiritually uncertain,” that offers the greatest insight into Canadians’ evolving beliefs and practices. The privately faithful, 30 per cent of respondents, “are people who actually believe in God, believe in heaven, believe in an afterlife,” said Angus Reid, the institute’s founder and chairman. “They have largely not been involved in organized religion. They will go to funerals and weddings and that sort of thing, but their faith is largely a private matter, and it’s really driven by their prayer. They pray on a regular basis.” Mike Faille/National Post//Angus Reid The spiritually uncertain, also representing 30 per cent, “seem to be a bit confused about where they want to be,” Reid said. “On some issues they kind of side with the non-believers, but they haven’t given up totally on everything. “They continue to believe that there’s a God, but they’re uncertain about the role of God.” The poll is part of a multi-faith effort initiated by Cardus called Faith in Canada 150, which aims to highlight the role religion has played historically and continues to play in Canada. The initiative, which has a budget of roughly $1-million, was denied federal funding as part of official 150th anniversary celebrations. Mike Faille/National Post//Angus Reid Results of the online poll offer reason for organized religions to be concerned. “The word ‘religion’ itself has become a little bit of a four-letter word,” Reid noted. When given a series of words and asked whether they had a positive or negative meaning, only 25 per cent of respondents said religion was positive, while 33 per cent called it negative. The words “forgiveness,” “morality” and “mercy” received the highest positive scores, while “evangelism” and “theology” were the lowest. “Some of the discomfort about some of the language does pose a challenge to faith leaders that perhaps they have not been as effective as they should at explaining themselves to their fellow citizens,” Pennings said. Mike Faille/National Post//Angus Reid The poll found significant variations across Canada’s regions. In the Prairie provinces, roughly 30 per cent of respondents were classified as religiously committed, compared with just 14 per cent in Quebec and 19 per cent in British Columbia. Reid said B.C. is “in many respects the most godless part of Canada,” with 27 per cent of its people falling into the non-believer category. Quebecers, while not committed enough to attend church, have not completely severed their deep religious roots. Only 18 per cent are non-believers while 36 per cent are spiritually uncertain and 32 per cent are privately faithful. “It’s not that Quebecers have totally given up on God,” Reid said. “They have given up on religion.” Across Canada, immigrants and visible minorities are much more likely to be religiously committed. Visible minorities made up 16 per cent of the sample group but accounted for 29 per cent of all religiously committed respondents. “The march toward secularism that has dominated Canadian society for the last couple of decades appears to be in a bit of a reversal and will be reversed over time if these trends continue, because clearly population growth is coming from immigration,” Reid said. Pennings said it would be a mistake to think that just because church pews have emptied, religion can be ignored. Mike Faille/National Post//Angus Reid “We’ve conditioned ourselves to think that faith is extremely private and personal and not something to be talked about in polite company,” he said. “The reality is we do that at our peril. Faith shapes how we relate to each other, and if we’re going to prosper as a society in the future we need to understand each other in a context of increasing faith diversity.” The online survey conducted from March 29 to April 3, polled a representative sample of 2,006 members of the Angus Reid Forum.

April 13, 2017

Ray Pennings: It is time to change the narrative around religion in Canada

Almost 150 years following Confederation, faith continues to play a significant and positive role in Canada’s civic life. Faith was a central part of the Canadian project in 1867, be it through recognition of religious freedom for Quebec’s Roman Catholics, the principles enshrined in Common Law, or by borrowing from the Book of Psalms for Canada’s official motto “From Sea to Sea.” Today, new polling by the Angus Reid Institute conducted in partnership with Faith in Canada 150, an interfaith initiative of think tank Cardus, finds only 19 per cent of Canadians identify as non-believers in any religion, while about 21 per cent are the direct opposite — religiously committed. The rest of Canadians call themselves either “privately faithful” or “spiritually uncertain.” They’re neither strong believers nor disbelievers. Despite this religious openness, the same polling indicates a significant disconnect between the perception and reality of faith’s role in today’s Canada. Simply put, religion has an image problem in Canada. In fact, the word “religion” is more likely to be seen negatively than positively, according to this new poll. Moreover, just over half of Canadians say they disagree with the claim that religion’s overall impact on the world is positive. About half of Canadians polled say they’re uncomfortable around those who are religiously devout. Throw in terms like born-again, theology and evangelism, and just 15 per cent of respondents associate those words with a positive meaning. But how well do Canadians actually understand the role faith plays in everyday life? Asked what’s most important in life, the 21 per cent of Canadians who are religiously committed are most likely to prioritize family life, honesty and concern for others. Conversely, concern for others was a lower priority for non-believers. Instead, they are more likely to select a comfortable life, self-reliance and good times with friends as important. Not to put too fine a point on it, but those who are most likely to pray to God, attend religious services regularly and read the Bible or another sacred text seem most oriented toward others and their welfare. What about Canadians’ emotional lives? The religiously committed are the happiest amongst us. Fully 47 per cent of them say they’re very happy or extremely happy overall, compared with 35 per cent of non-believers. They also report the highest levels of happiness among friends and in their communities. None of that is terribly surprising. If anything, it simply confirms what other research has shown. It makes sense, then, that the religiously committed are also more likely to be “very optimistic” about the future. When it comes to community engagement and charitable giving, once again it’s the religiously committed who report the strongest involvement. Slightly more than half of non-believers say they are uninvolved in community groups or activities. That percentage drops to 17 per cent of the religiously committed. In fact, 41 per cent of the religiously committed have at least some involvement in their community, with another 42 per cent reporting heavy involvement. Almost a third of the religiously committed say they regularly volunteer compared with 13 per cent of non-believers. Dare we ask about charitable giving? Only 12 per cent of non-believers say they try to donate to whatever charities they can. That jumps to 43 per cent among the religiously committed. These are not selfish people. The numbers present a clear picture: Religiously committed Canadians tend to be the most concerned about others, the happiest and most generous. So, why do Canadians have a negative view of religion? Arguably, the story of faith in Canada is not being well told. The narrative around faith is often negative. Religion is frequently presented as something that divides rather than unites people within communities. That is part of the reason why Faith in Canada 150 exists, to showcase the role of faith in making Canada the country that it is. That legacy is a story worth telling. Ray Pennings is executive vice-president of think tank Cardus. Mike Faille/National Post//Angus Reid

April 13, 2017

Doubting Thomas redeemed: Once an obstacle, skepticism is now seen as a stepping stone to faith

Easter is an awkward time for the faithful skeptic, much more than Christmas. Even with its backstory of maternal virginity, the Christmas story does not especially strain credulity. It is a plausible sequence of events. A child is born in a stable, some rich guys show up with presents, local shepherds have a wild experience overnight on the hills. It would not be the first time. But the elaborately impossible Easter story demands a longer leap of faith, far beyond the scene-setting earthquake, the curtain tearing in the Temple, the saints rising from their graves, to the grandest invitation to skepticism ever — the empty tomb. The man who has come to embody this commonsensical squinty-eyed view of the Easter tale is known as Doubting Thomas. It is not a term of Christian affection. He is meant as a cautionary tale. One of the 12 apostles, Thomas missed the moment when the risen Jesus first appeared to the others, and he would not believe in this resurrection until he felt the nail holes himself and even put his finger into the wound on Jesus’ side from the soldier’s spear. This incredulous gesture, almost defiling the body of Christ to satisfy his own intellectual desire for proof, became Thomas’ traditionally unsympathetic rendering in classical art. After the scorn and mockery of Jesus’ persecution and trial, this was the newborn Christianity’s first internal encounter with skepticism, and typically, it was brushed aside with shame and stigma. By his failure, Thomas became the odd one out. As Jesus put it, throwing some of his trademark shade: “Thomas, because thou hast seen me, thou hast believed: blessed are they that have not seen, and yet have believed.” “Doubting Thomas seems to have been devised by John (in his Gospel, the only one that tells this story) largely in order to invoke, exaggerate and then resolve doubt, and thereby to lay doubt to rest once and for all,” wrote Glen W. Most, professor of social thought at the University of Chicago, and of Greek philology at Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa, in his book on Thomas. “Yet once Thomas has been invented, he is not so easy to get rid of: he lingers on, like the shadow of a guilty memory.” The traditional moral is that Thomas had the wrong reaction. He should not have needed proof. Faith is a virtue precisely for this reason. Over the centuries, this view has softened, and Christianity has made a kind of peace with its doubters. Skepticism has repeatedly shown its value as an intellectual tool, even for believers. Rather than an obstacle, doubt has been recast as, if not exactly a virtue, at least a stepping stone to faith. The stigma of doubt is weakening and as it does, Thomas is slowly redeemed. Doubt is a key part of the modern Canadian experience of faith, according to a joint polling project of the Angus Reid Institute and Faith in Canada 150. Even on the basic question of whether they believed in God, a majority of people who identified as “privately faithful” answered “yes, I think so,” which was almost exactly the same proportion as those who identified as “spiritually uncertain.” Even some of the self-professed non-believers fudged it, with more than a third declining to give the firm atheist response and instead saying, “no, I don’t think so.” Mike Faille/National Post//Angus Reid Ironically, there may be a lesson in all this for science and the other great mysteries of human inquiry that inspire wonderment and doubt — physics, life’s origins, climate change, consciousness. After centuries of institutional stubbornness, Christianity, Catholicism in particular, has largely resolved itself with the pursuit of knowledge through skeptical science. The 20th century marked an important moment in that shift, as evolution and physics, backed by evidence and theory, caused crisis for the Christian creation stories. Theologically, the threat was little different than in the 17th century when Galileo argued the Earth orbited the sun, not vice versa. But the reaction could not have been more different. Galileo was called a heretic and died under house arrest. But Pope Pius XII’s response in the 1950s to the idea that the universe originated in the Big Bang was almost embarrassingly enthusiastic and credulous. He wrote that science, “by going back in one leap millions of centuries, has succeeded in being witness to that primordial Fiat Lux (Latin for “let there be light”) when, out of nothing, there burst forth with matter a sea of light and radiation, while the particles of chemical elements split and reunited in million of galaxies… Hence, creation took place. We say: therefore, there is a Creator. Therefore, God exists!” Getty ImagesNor is it contradictory for a Catholic to believe in evolution, so long as it does not lead to denial of the immediate creation of souls by God. This modern position of the Vatican is what the evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould described as NOMA, the view that religion and science are Non-Overlapping Magisteria, each asking different questions that cannot be answered in terms of the other, however tempting it may be to try. Pope John Paul II recognized this and formally acquitted Galileo in 1993, acknowledging he was correct. Modern science could learn from religion’s experience of being put in its place. Though the philosophical attitude of skepticism dates to Ancient Greece, Prof. Most points out that until modern times it was “sporadic and culturally marginal.” It was not really until the 17th century French philosopher René Descartes devised his famous thought experiment — doubt everything, then see what remains certain, which he took to be his own thinking self, or as he put it, “cogito ergo sum,” I think, therefore I am — that radical, principled doubt started to really show its usefulness. Skeptics started to be lionized as intellectual exemplars, from French Catholics like Michel de Montaigne to American atheists like H.L. Mencken. Now, virtually all academia is based on skepticism. Every field of inquiry has felt its withering glare and been forced to justify its foundational tenets. Some squirm more than others. But for many fields, the skeptic is now regarded less like the brave child who declares the emperor naked and more like a figure of scorn, suspected of stupidity or ulterior motives. In climate science, skeptics are oil industry shills or alt-right culture warriors. In evolution, they are biblical fundamentalist creationists. In physics, they are contrarian cranks. Partly this shift reflects the modern democratization of science, with more people taking part in scientific debates at various levels of sophistication. Partly it reflects the rise of the academic specialist, to whom the layperson can defer without actually understanding. And partly it reflects the role of science in informing the policies of governments, which want more certainty than science can usually offer. There can be an arrogance in certainty, all the worse when it is revealed as a pose, unjustified or poorly informed. Even when science cannot provide satisfactory answers — Why is there more matter than anti-matter? How did life begin? How does a material brain produce the subjective experience of thought? — those who are openly skeptical of the textbook answers are lonely voices among a faithful mainstream, and they are shamed for it. Christianity neutralized the threat of Thomas’s skepticism by eventually embracing it, by realizing that doubt can strengthen faith just as it reinforces knowledge. As Prof. Most put it, he is “a character with whom all modern readers can identify. Thomas stands for us.”Mike Faille/National Post//Angus Reid

April 13, 2017

Cardus’ Give 150 campaign tries to make charity a habit

Charity can be habit-forming — at least that’s the hope of the Christian think tank Cardus. To try out the theory, Cardus has launched the Give 150 campaign, designed to create a life-long giving habit with the help of a dollar-matching incentive and a patriotic pitch as Canada celebrates its 150th birthday. “It is a pilot project that we’re advancing to try to encourage Canadians to build that habit of giving,” said Michael Van Pelt, Cardus’ president and CEO. “The theme of Give 150 is really a way of saying giving as a habit will make this country a better country. Both giving financially and volunteering are key components to making this country the great country that it is.” The pilot project, which will continue for the duration of 2017, has a goal of seeing at least 2,500 Canadians create online accounts with Give 150’s partner Vancouver-based Chimp, an online charitable giving assistant account. From a Chimp account, participants are able to direct donations to any of Canada’s registered 88,000 charities. According to Chimp’s founder and CEO John Bromley, the current approach to raising money for charities fails to create repeat benefactors. “Today Canadians only give if they are asked,” said Bromley. “While fundraising is a critically important part of the charitable sector, and always will be, it has failed to create sustainable and cost effective cultural charity. (So) I started Chimp to provide an accessible and practical solution for people who have something they want changed in the world and have something to give towards it.” A Chimp account costs nothing to create and maintain. In fact, for the time being, simply opening an account as part of Give 150 will generate donation dollars. “The minute you sign up you get a gift of $15 and the minute you make your own contribution to your own charitable account you get another match of $15,” said Van Pelt. “And then if you actually make a commitment to reoccurring gifts then you get another match. It is just a really cool idea.” An anonymous philanthropist has put up $150,000 to fund the matching gift pool. “It is a really interesting initiative on the part of this philanthropist who is basically saying I want to create mechanisms and encouraging ways for everyday Canadians to give and to give habitually,” said Van Pelt. “It is not an easy challenge.” Since launching in 2013 Chimp has facilitated more than $200 million in donations, half of that money in the last year alone. Donations have ranged from a massive $4 million injection to more modest $15 donations. Among the most popular charitable sectors are religious organizations and orders, education, health care research, social services and poverty reduction, noted Van Pelt. He likened the creation of a Chimp account to establishing a personal charitable foundation. “You just jump onto your own personal Chimp account where you have money that you’ve already given, make donations to the organizations that you see fit and make your own charitable priorities,” said Van Pelt. “It is actually literally a charitable bank account for an everyday Canadian.” At the end of the year, Cardus will collect aggregate data from Chimp and then process that information. “Who knows what we will learn out of this,” said Van Pelt. “But someone needs to take up the challenge of this and what better time to do it than as we celebrate Canada 150.” Much of the challenge facing the charitable sectors, according to Statistics Canada, is the declining number of donors. Statistics Canada figures show that while the total dollars increased 14 per cent between 2004 and 2013, to $12.76 billion, the percentage of adult donors declined from 85 to 82 per cent. Van Pelt said Canadians should be concerned about this downward trend on donor numbers. “It will not be good for Canada if we keep seeing a decrease in giving,” he said. “Giving needs to be a muscle that will energize and maintain the vibrancy of the many charitable organizations across this country that are so important. If you live in a small town or live in a city, just look at the numerous charitable organizations.” Michael Fullan, executive director of Catholic Charities which oversees the allocation of donations to two dozen social service agencies in the Toronto archdiocese, said the trend poses a very serious threat to Canadian charities as the older generation becomes unable to contribute. “When you look at the older generations, those people are not going to be in a position to keep giving,” said Fullan. “They are going to pass on, retire or just have fewer resources. It is a real threat.” What’s needed is a change in the culture of charity among younger Canadians, he added. “I really applaud this (Give 150) kind of initiative,” he said. “It is a very good idea, whenever you have an opportunity, to cultivate a spirit of giving because you build seeds that will continue to grow in the future.” For further information visit www.faithincanada150.ca/give150.

April 6, 2017

Canadians’ religious tolerance changing, but prejudice still exists toward Islam

To read the article, click here .

April 5, 2017

Canada’s religious landscape is changing…

To listen, click here .

April 4, 2017

Keeping the faith alive

Faith in Canada 150 seeks to answer the question of how we live together in our differences and learn not just tolerance but love and neighbourliness, an aim that seems increasing vital today.To read the article, click here

April 3, 2017

Milton Friesen in Engage!: The Halo Project

April 3, 2017