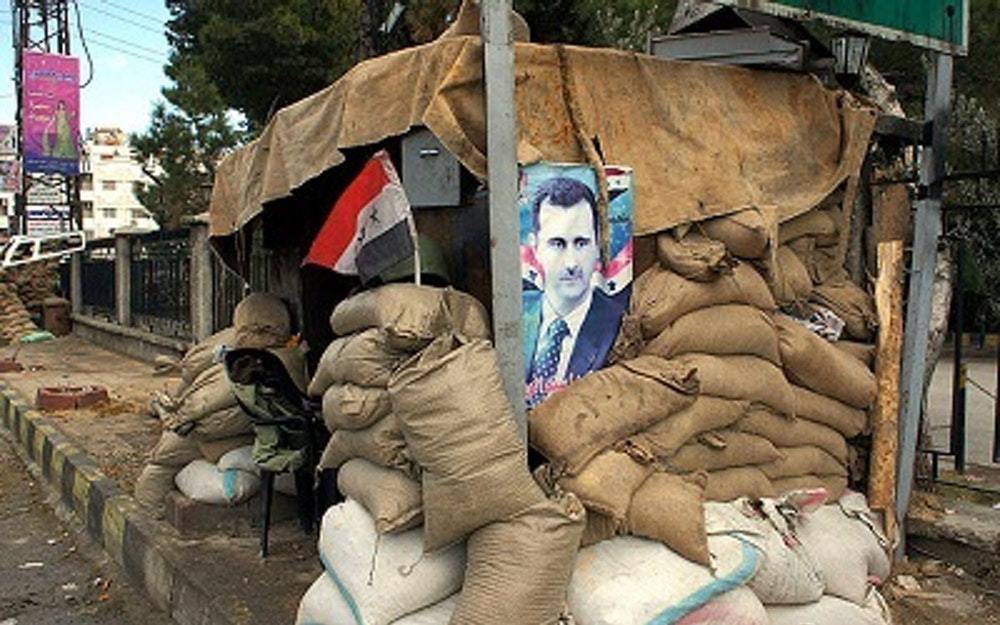

On Saturday, the Arab League finally recused itself from what had become a perfunctory observation of atrocities in Syria. At least 80 people were killed in recent days, and the United Nations estimates that at least 5,400 people have been massacred by the regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad in the last 10 months. Is it time for military intervention? Could Western Christians justify such involvement? Should they be calling for it? The Arab League’s Secretary General, Nabil Elareby, blamed Damascus for the spike in bloodshed, saying the regime has “resorted to escalating the military option in complete violation of (its) commitments” to end the crackdown. He said the victims of the violence have been “innocent citizens,” in an implicit rejection of Syria's claims that it is fighting “terrorists.” Backstopping this criminal tyranny is Damascus’ rejection of the Arab peace plan and, more significantly, Russia’s threat to veto at the U.N. Security Council to protect Syria. And still, though it seems a callous and brutish thing to say, there is no just case for intervention in Syria - yet. Hope lies in the unification and recognition of a fractious Syrian resistance. A just intervention, or a just war, is an ancient inheritance of Christian political thought, from Augustine, through Aquinas and forward. Christians have always struggled with the twin moral call of charity balanced by the realisms of their day: what can practically be achieved, with limited resources, in often tragic circumstances. Just war is a way of faithfully calculating a terrible process of global triage. And just war demands, a la jus ad bellum, that the justness of an intervention, of any military action, must be judged not merely on moral outrage, right and true as that outrage may be, but on the probability of success and the exercise of prudent proportionality. Justice can never be predicated on short-term sentimentality. It must have a long game. The long game in Syria looks bad, maybe worse, after intervention than before. Parallels abound between Libya and Syria, but Syria is not Libya. Syrian opposition is divided and weak. Unlike the Transitional National Council in Libya, which gained fast international recognition, the Syrian National Council (SNC) took seven months to form and has received almost no recognition. The fracture is endemic in mixed calls from the SNC for Western intervention, first in favor, then denounced, then called for again. The Free Syrian Army (FSA), an armed resistance, has on its own terms called for a Western campaign. It is not the only armed force. Scores of rebel brigades, not beholden to either the FSA or the SNC, struggle on in the urban jungle of Syrian resistance. There is no front line between opposition and Assad forces that can be separated by air power, no armored columns driving along empty desert roads to be targeted by the West’s deadly drones. Syria’s killing fields are dense urban environments, nested in a region with extremely high probability for spill over into Israel, Lebanon, Turkey, Jordan and Iraq. Syria’s staunchest ally, Iran, is in its own ill-fated game of brinkmanship with global powers over its nuclear program. Justice can never be predicated on short-term sentimentality. It must have a long game. A no-fly zone, or any exercise of air power, would mean enormous collateral damage, in both civilian lives and infrastructure. Syria’s anti-air and military generally have not defected en masse like Libya’s. And if, from the ashes of a Syrian intervention, Assad were to be overthrown, there is very little enthusiasm today that one of the many competing factions could practically dominate. More likely, fringe groups currently allied with the regime would seize control of convenient strongholds and Syria would be gripped in a civil war, becoming a harbor for Hezbollah, the Kurdistan Workers Party, Iraqi pro-Iranian forces and Iran’s Revolutionary Guard Corps, agents of which are already embedded with Assad’s feared Fourth Armored Division. Syria would become yet another proxy war zone. “Damascus has scandalized every Potemkin effort at reform or negotiation,” says Michael Weiss in Foreign Affairs. Assad will find no peace in the international system, but 23 million Syrians still might. For that to happen, before a just war or responsibilities to protect can be exercised, a galvanized Syrian opposition must take form. A post-Assad future is possible if the international community - especially the Security Council, the Arab League and the people of Syria - work to form a beachhead of goodwill for a united, globally recognized resistance. Military intervention today appeals to the soul, but not to the senses. This doesn’t mean ignoring a slaughter, but it does mean working prudently, multi-laterally and - especially - indigenously to support, not manufacture, a united cause of Syrian freedom.

Cardus researches value of Christian education

February 1, 2012

Seeking justice for Syria

January 29, 2012

Brinkmanship with the Desperate: Now is not the time to attack Iran

Monday’s announcement by the European Union to embargo Iranian oil further hamstrings an already crippled Iranian economy. Iran is a country, argues Fareed Zakaria, growing in desperation. E.U. oil imports represent 600,000 barrels per day, or 26.3% of Iranian exports (WSJ). The game of brinkmanship in the Strait of Hormuz, between forty thousand U.S. troops stationed in the Gulf, accompanied by strike aircraft, two aircraft carrier strike groups, two Aegis ballistic missile defense ships, and multiple Patriot anti-missile systems is a badly fated gamble. It gets worse. Read the rest of the article at Capital Commentary.

January 27, 2012

Who will replace “the church ladies”?

Mark Forsythe of CBC Vancouver's B.C. Almanac plays a pre-recorded conversation with Cardus Director of Research Ray Pennings, on the declining civic core of volunteers. Listen to the clip here:

January 27, 2012

Cardus Education Survey

January 19, 2012

Law, Religion and Public Reasoning

Abstract A forceful recent opinion on law and religion by Lord Justice Laws in a religious discrimination case has drawn renewed attention to two principles often supposed by liberal legal and political theorists to be essential foundations of liberal democracy: the principle of state ‘neutrality’ towards religion; and the principle that public reasoning must be ‘secular’. This article argues that, while the first principle is defensible, the second principle is invalid and illiberal, and proposes a conception of public reasoning that permits, indeed positively encourages, the invocation of religiously based reasoning in ‘representative’ political speech. The first part of the article briefly states the central argument advanced in favour the principle of secular public reasoning, and its corollary, the ‘principle of restraint’ on religious reasons. In the second part, three widely invoked critiques of the principle of restraint are reviewed. The third part proposes that religiously based public reasoning is entirely compatible with, indeed enjoined by, the type of representative public speech that should characterize a confident liberal democracy. It also argues, however, that the first principle, state ‘neutrality’ towards religion (rightly understood), rules out explicit public appeal, by state officials, to religious reasons in justifying laws. Read the entire article online here.

January 16, 2012

Who will take up the mantle of the church lady?

When my mother, a youthful 88, poured her last cup of tea as president of her local Anglican Church women’s organization last year after 19 years at the helm, the group also went into retirement. Many of its former members had died or were in nursing homes by then, and there was no one able or willing to take on the rigours of making sandwiches for funerals and organizing fundraising bazaars. After more than a century, the organization that had been home to generations of volunteers, was no more. Read the entire article.

January 12, 2012

New year, ancient resolutions

Guy Nicholson: Thanks for joining us today, panelists. Which of these words with religious connotations comes closest to the secular New Year’s resolution: atonement, forgiveness, confession, reincarnation? Peter Stockland: Well, I would say they are all part of the same process, so it is hard to pick one out. Before we are genuinely renewed (reincarnated?), we have to seek genuine recognition (atonement) of what we’ve done (or are doing) in error and in both Catholic tradition and, I think, standard behaviour-change theory, we have to admit the error out loud to seek forgiveness and so let past patterns go. We begin with recognition, move to expression and get to renewal or resolution. My resolution this year, by the way, is to answer questions more directly. Sheema Khan: I think forgiveness is the closest, in the sense that one seeks forgiveness from God (for past transgressions), and one also forgives oneself. Of course, if the resolution involves changing one’s behaviour toward others (e.g., renewing family relationships), then a good way to start is to seek forgiveness of those whom one has hurt. Forgiveness is mentioned often in the Koran, and Muslims are reminded: “Forgive, do you not want God to forgive you?†Sincere forgiveness implies a change of behaviour as well. Lorna Dueck: What a great way to start us off, Guy. I think the word “confession†best suits the New Year’s resolution. In Christianity, confession can mean letting go of our sin, and it also means stating a belief we want to own. Confession is a new beginning! Peter Stockland: With perhaps the qualifier, Lorna, that Christian confession, like a New Year’s resolution, requires a concrete act (penance) to stick. We can't just have to say, “Oops, sorry about that.†We have to own it and take steps to change it. Read the entire exchange.

January 9, 2012

Let’s let religion out of the closet

Pennings quoted in the Toronto Sun, "Let’s let religion out of the closet" Ray Pennings of Cardus, an independent policy institute, says religion generates: “A civic oxygen on which Canadian social ecology relies. “The Canadian Centre for Philanthropy calculates that the 32% of Canadians who are religiously active contribute 65% of direct charitable donations.†He addressed the danger of excluding religion in a way people concerned with human rights and empowerment of the individual should understand. “If public, political language can only exclude God, we are not just preventing believers from speaking about their faith. We are denying them the right to speak for themselves.†Read the entire article.

January 9, 2012